The literary hoax has a long history, going back as far as the fourth century BC, as writers from the ancient world to the present play games with authenticity and authorship (Katsoulis 1). In the Australian context, the hoax modernist poet Ern Malley is frequently invoked to contextualise more recent examples of trickery, such as the appropriation of Indigenous voices by non-Indigenous writers, or the assumption of a falsified ethnic identity as author (Nolan and Dawson; Takolander and McCooey). Most recently, accusations of plagiarism in John Hughes’ novel The Dogs (2021) have included comparisons to Malley as a means of debating ‘good modernism and bad modernism’ and the use and misuse of quotations and allusions (Marks). Instead of focusing on the local context, however, I propose a transnational reading in which McAuley and Harold Stewart’s Ern Malley poetry The Darkening Ecliptic (1944) is read alongside Max Aub’s fake biography of Catalan modernist painter Jusep Torres Campalans, first published in Mexico in 1958 as ‘an extraordinary work of non-fiction’ under the author’s own name (Faber 237). Pairing these ‘apocryphal artists’ responds to Robert Dixon’s advocacy for Australian academia to engage with ‘non-Anglophone traditions’ as part of ‘cross-cultural comparisons’ (17). Jusep Torres Campalans 1 is a little-known but fascinating text which, like The Darkening Ecliptic, represents a ‘provincial’ response to modernism from the margins. The intention here is to recontextualise the reception of Ern Malley within a transnational frame, as a ‘black swan of trespass on alien waters’, which resonates beyond Australian shores as an apocryphal modernist yearning for recognition.

In order to avoid the pitfalls of simplification in comparing works from different times and places, this essay utilises the literary technique of parataxis. Susan Stanford Friedman demonstrates this technique in Planetary Modernisms, whereby texts from different cultures are paired to highlight the ‘mutually constitutive nature of different modernities in the recent colonial and post-colonial eras.’ Friedman’s intention is to rethink ‘binary approaches to transnational modernity and modernism’ (12). In this case, by pairing texts with Australian and Catalan subjects as literary hoaxes, the story of a simplified, belated modernism in Australia can be challenged. Ken Gelder’s notion of a ‘proximate reading [as] … a way of conceptualizing reading and literary writing in contemporary transnational frameworks’ provides a conceptual methodology (1). Here ‘connective tissues’ are the focus, as the reader negotiates ‘relationships between origin and destination, what is close and what is distant’ (4). Gelder writes,

As a literary trope, Australia is itself ‘just one code book among many’, routinely criss-crossed by other literatures, localized in some instances and woven into transnational semantic networks in others. (14)

Gelder connects ‘proximate reading’ to Friedman’s definition of parataxis, as a means of reading ‘alongside’, that is, ‘re-engaging with the issue of proximity, providing a “criss-crossing set of pathways” that may also, in fact, not criss-cross at all’ (11). The literary hoax is one such ‘semantic network’ where considerations of proximity can stimulate a wider, transnational understanding of both ‘poet’ Ern Malley, and ‘painter’ Jusep Torres Campalans as ‘apocryphal artists’. Significant differences in the art, deception and reception of the apocryphal modernists are acknowledged at the outset. As such, this essay reflects the type of ‘collage’ Friedman refers to as ‘a kind of comparative work based in a recognition of the in/commensurability of the texts set in conversation’ (281).

Literary hoaxes take different forms, from the ‘genuine hoax’ which was never intended to be revealed, to the ‘prank text’ where a revelation is intended, to the ‘mock hoax’ wherein a literary writer ‘plays conscious tricks with the very notion of authorship’ (Katsoulis 2–4). Ern Malley is a prime example of a prank text intended to lure a response, to mock the sensibilities of a literary community (in this case, the editors and readership of the 1940s Adelaide literary journal The Angry Penguins). The subsequent court case is a unique instance of the public prosecution of poetry in the Australian context, as well as being ‘the most spectacular Australian instance of poetry being thrust into an extra-literary cultural context’ (Mead, Networked 110).2 Max Aub’s apocryphal biography of a fictitious painter – a ‘friend’ of Picasso and one of the unacknowledged founders of Cubism – is arguably both prank hoax and mock hoax: it includes discoverable falsehoods (such as exhibitions of Aub paintings in real galleries) and is also a self-consciously deconstructive text in which Aub appears as both character and writer.

In addition to larger, historical surveys of the field (Katsoulis; Miller), the literary hoax has been the subject of study from a variety of contemporary critical approaches. Chris Fleming and John O’Carroll argue, after Jacques Derrida, that ‘the hoax is a deconstructive structure that inhabits what it attacks’, while its ‘performative’ elements often form part of a didactic strategy (46, emphasis in original). Similarly, Eckart Voigts-Virchow analyses the ‘performative hermeneutics’ of the text in relation its ‘cultural moment’ (180). Joy Williams and Louis Menand focus on the ethics of authorship, particularly the ‘autobiographical pact’ which represents a ‘tacit understanding that the person whose name is on the cover is identical to the narrator, the “I”, of the text’ (68). Ern Malley is discussed as a key text in each of these articles, with Williams and Menand citing Robert Hughes’ description of Malley as ‘the literary hoax of the twentieth century’ (72, emphasis in original), and Voigts-Virchow tracing its international reach as it ‘migrated’ to England and America (179).

Both texts challenge the authority of European modernism from the margins. However, while The Darkening Ecliptic is largely a poetic endeavour with some biographical dimensions, Jusep Torres Campalans focuses primarily on the artist’s biography, while including representative art within the text. Cultural differences also emerge in how the texts have been received over time. While Fleming and O’Carroll connect The Darkening Ecliptic to the ‘belated arrival’ of modernism in the Australia context (32), the reception of Jusep Torres Campalans within the Hispanic tradition is notably different. Recent scholarship questions ‘the suitability of the concept of [m]odernism as applied to Spain’, arguing for the differences between modernism, modernismo, and the Spanish avant-garde. The authors of a ‘many voiced essay’ which followed an international symposium on the topic expressed regret for the ‘peripheral space’ Spain occupies within studies of modernism, ‘dominated by those who see the culture of the period through an Anglo-American lens’ (Herrero-Senés et al. 162-164). Rosell’s extensive study ‘Spanish Heteronyms and Apocryphal Authors’ places Aub within an Iberian tradition of ‘literary heteronyms … [in] poetry, prose and painting’ (115). For example, Rosell notes that Portuguese poet and critic Fernando Pessoa’s ‘Tábua Bibliográfica’ (1928) invented ‘an assemblage of undiscovered poets marked by an unprecedented discovery of the master he had within himself’ (122). Rather than being a source of embarrassment as indicative of an insular response (as in the Australian context [Cooper 317]), Pessoa is represented positively as an artist who ‘created poets’, to bring a specific future literary tradition into being.

By contrast, a shorthand description of the emergence of Ern Malley as hoax poet is followed by a customary lament for ‘the philistine nature of this nation’, with the hoax viewed as a setback to ‘the local acceptance of modernism’ (McDonald 64). Clearly, this need not be the case: it is possible to read The Darkening Ecliptic as part of an antipodean tradition, and as part of a local conversation with modernism, demonstrated by the Australian poets John Tranter and Phillip Mead’s placement of Malley at the centre of the Australian canon, in the 1991 Penguin Book of Modern Australian Poetry (Coleman). As Jahan Ramazani writes, we need to break away from dichotomous approaches which position ‘models of tradition as either [T.S.] Eliot’s “mind of Europe” or its postcolonial obverse’ in favour of ‘mutually transformative relations between the poetries of the metropole and margin’ (460). Pairing Ern Malley and Jusep Torres Campalans as invented artists responds to this entreaty, as texts from the ‘margins’ representative of ‘mobile, interlocking, yet distinct modernisms’ (Friedman 216). A paired, proximate reading encourages a reconsideration of distance from traditional centres of modernism. In their introduction to Modernism and Its Margins, Geist and Monleón describe the position faced by progressive artists and intellectuals in Valencia in the 1930s: ‘What they ultimately came to theorize was that modernisation implied never reaching modernity: from Cullera to Valencia, to Barcelona, to Paris . . . the modern resided always somewhere else’ (xviii). To theorise a ‘provincial avant-garde’ means ‘acknowledging such a distance’ – a distance shared by ‘Australian poet’ Malley and exiled ‘Catalan artist’ Campalans, found living ‘under a palm-thatch roof’ in the mountains of Mexico’s Chiapas (Aub 13).3

The Darkening Ecliptic

The central premise of the literary hoax behind the publication of ‘The Darkening Ecliptic’ is the proxy figure of Ern Malley as ‘antipodean genius’, a local poet who died at the age of twenty-five (the same age as Keats) but left behind a unique treasure: a mini-manifesto and a collection of sixteen eccentric works of imagist verse. Ken Gelder writes that ‘proximate reading is a kind of allegorising practice, an act of proxy where one thing can stand for another’ (6). The intended comedy here centres on the unlikely hero, in which Malley allegorises an embarrassing, working-class Australian culture, one shown to be aping the imperial centre. Proximity is also the allegorical stretch between Sydney and London (via Adelaide) as Angry Penguins editor, Max Harris, reaches out to English art historian and poet Herbert Read for reassurance. Read obliges with a fulsome statement of support once the hoax is exposed:

If a man of sensibility, in a mood of despair or hatred, or even from a perverted sense of humour, sets out to fake works of imagination, then if he is to be convincing he must use the poetic faculties. If he uses these faculties to good effect, he ends up deceiving himself. So the faker of Ern Malley. He calls himself ‘the black swan of trespass on alien waters’ and that is a fine poetic phrase … (‘Malley’, 17).4

The Angus and Robertson 1993 publication of The Darkening Ecliptic – Ern Malley withholds the author’s names, reflecting the fact that McAuley and Stewart never claimed copyright on the poems, and – as Max Harris remarked – ‘Ethel [Malley’s ‘sister’] wrote us a letter giving us complete rights in the poems’ (Heyward xix). This playfulness with fictional elements continues with the inclusion of Ethel’s letters. The first letter consists of three paragraphs and the bait: two Malley poems. As ‘biographer’, Ethel has a modest, suburban voice. Duty motivates her actions: ‘I am not a literary person myself and I do not feel that I understand what he wrote, but I feel that I ought to do something about them’ (‘Malley’ 8).

The second letter, which arrived with the rest of the poems at Harris’s request, summarises Malley’s short life. Born in Liverpool (England) on 14 March 1918, his family migrated to Australia, where they resided in Petersham. He worked as a mechanic after leaving school before moving to Melbourne, where he sold life insurance for National Mutual. He passed away on 23 July 1943 from Graves’ disease and was cremated at Rookwood Cemetery. Here the hoaxers have Harris in their sights. Previously, Harris had lamented feelings about his ‘hopeless Australian heritage’; while Harris’s politics ‘were firmly, fashionably, left wing’ (Heyward 21, 25). A working-class Australian genius-poet was attractive bait for this type of ‘show and reveal’ hoax. Of the literary effort behind the construction of the character of Ethel Malley, Stewart once said that the letters required ‘much more literary skill and much more time and trouble … than did the actual poems themselves’ (130). Even if this is overstated, the biographical sketch of Malley is a key element supporting its cultural reach. Sidney Nolan painted a series of ‘Erns’ in the 1970s, including his oil portrait ‘Ern Malley’ (1973) in military uniform. John Tranter’s 2006 ‘The Malley Variations’ consists of ten poems that form a conversation with the imagined artist. Other appropriations include Garry Shead’s etchings (2006), and Peter Tahourdin’s theatre-music piece (2007). As Mark Osteen has written, ‘[l]ike Frankenstein’s creature, Ern became an unkillable monster who would forever haunt his heedless parents’ (360–361).

Harris’ essay ‘The Hoax’ quotes in full the press statement put out by McAuley and Stewart on 5 June 1944, which details their intentions in undertaking ‘a serious literary experiment’ aimed at testing the taste of those who symbolise ‘an Australian outcrop of literary fashion’ (that is, modernism, with ‘outcrop’ connoting provincialism). The letter indicates a deliberate methodology but claims that the poems have no psychological value and are ‘utterly devoid of literary merit’ (‘Malley’ 11–14). Yet despite such declared intentions, Harris argues for the cultural significance of Malley, since ‘personal myth can be realised in and through environment’. Key painters listed in support of this notion include Arthur Boyd, Fred Williams, John Olsen, Albert Tucker and Brett Whiteley. Harris is defiant: ‘… The Australian imagination is its own and recent thing. It is ours. It is true. It is what we give out to the world, and the world finds worthy’ (27).

John McDonald has written wittily, ‘Ern Malley is probably the most widely discussed Australian poet of the twentieth century. The fact that he never existed has done little to damage his popularity’ (63). However, whereas Aub’s Jusep Torres Campalans has been analysed in some detail as a literary text (Faber; Rossel; Leal-Santiago), it is only relatively recently that the Malley poetry rather than the hoax has become the focus of discussion. Writing in the year 2000, David Musgrave and Peter Kirkpatrick stated that (at the time) no one had offered a ‘detailed analysis of the text of the Malley poems, possibly because they remain unfriendly to older formalisms, and unuseful [sic] to contemporary cultural studies’ (131). Musgrave and Kirkpatrick’s solution is to read the poems through a critical lens, namely Deleuze and Guattari’s notion of ‘minor literature’. A critical strategy also inspired Fleming and O’Carroll’s deconstructive reading of Malley as ‘performative hoax’. Heyward at least starts an analysis by tracing exact rhyme choices to Walter Ripman’s A Pocket Dictionary of English Rhymes (1932). Literary allusions are also noted, such as ‘seed-puffing thistle’ in ‘Petit Testament’ as referencing John Keat’s ‘seeded thistle’ (‘A Portrait’). Subsequent studies of the Malley poems include Philip Mead’s Networked Language (2008) and David Brooks’ The Sons of Clovis (2011). Mead devotes the last third of his lengthy chapter ‘Poetry and the Police’ to a close reading of Malley poems, particularly ‘Sonnets for the Novachord’ and ‘Young Prince of Tyre’ (152–185). Shakespeare’s Pericles is a key source of intertextual allusions, as Mead demonstrates, concluding amusingly that Malley is both national poet and ‘Australia’s Shakespeare’ (185). Brooks reads the Malley poems in some depth to explain the literary quality of the hoax, building a case for the influence of Adoré Floupette’s 1885 parody, ‘Les Déliquescences’ (2008).

As a known hoax text, it requires an active imagination to read The Darkening Ecliptic as authentic modernist verse. Yet as Ross Chambers argues, this ‘bone of contention’ in the hoax is still current: ‘What I make of, or with, the Malley corpus depends entirely on whether or not I acknowledge its claim to be poetic speech’ (38). The Malley preface includes seductive aphorisms (‘Every poem should be an autarchy’), a teasingly short biography (‘There is no biographical data’), and hints at influences (‘objective allegiances’ [30–31]). The first poem ‘Dürer: Innsbruck, 1495’ introduces the figure of the scholarly monk, ‘cowled in the slumberous air’, eyes-closed, as the reader is transported to earlier times, quickly relaying a sense of belatedness and distance. A series of images develop this idea: ‘I have shrunk to an interloper, robber of dead men’s dreams’; ‘the mind repeats … the vision of others.’ The final line of this poem can be read as an ironic comment on feelings of antipodean inauthenticity when compared to the imperial centre: ‘I am still / The black swan of trespass on alien waters’ (32). Gelder writes that ‘citations are themselves expressions of proximity’ (5); this is evident in subsequent poems continuing this conversation with Europe through various acknowledged ‘Masters’. Renaissance artist Albrecht Dürer, referenced in the title of the first poem, recurs in ‘Documentary film’ in the phrase ‘“Sampson killing the lion” 1498’ (42) – a woodcut part of Dürer’s apocalyptic series. Keats ‘repeats’ in ‘Colloquy with John Keats’, while ‘Petit Testament’ references Shakespeare’s ‘The Phoenix and the Turtle’ (‘Perched in the sole Arabian tree’ [60]). ‘Sweet William’ (36) alludes to William Wordsworth and continues the image of antipodean inversion: ‘My white swan of quietness lies / Sanctified on my black swan’s breast’ (36). Keats’s famous statement, ‘Beauty is truth, truth beauty’ from ‘Ode on a Grecian Urn’ becomes the subject of a funfair spinning wheel (‘Look! My number is up!’ [57]), along with a conversation about ‘Beauty’ in which ‘Malley’ says (as if speaking to Keats), ‘Like you I sought at first’ (58). In ‘Petit Testament’, Shakespeare’s Arabian tree is juxtaposed to the local eucalypt: ‘Here the Tree weeps gum tears / which are also real: I tell you / These things are real’ (60). In each case, there is an ironic tone and self-referential localism, as literary citations connect ‘Ern’ with key texts in English literature.

A poetic conversation with Anglo-American modernism (i.e., modernism as conceived at the time) is also present in allusions to T.S. Eliot as a form of indirect citation. The title ‘Perspective Lovesong’ surely references ‘The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock’, with parodic Eliot allusions in the same poem. ‘I must go with stone feet / Down the staircase of flesh’, for example, appears to echo, ‘Let us go then, you and I’ and ‘Time to turn back and descend the stair’ (from stanzas 1 and 4 of ‘Love Song’). Tijana Parezanović writes that the Malley poems ‘clearly imitate the style of the leading modernist poets’, with ‘Documentary Film’ drawing on the ‘broken images’ from Eliot’s ‘The Waste Land’. For example, ‘the sound track like a trail of saliva’, Parezanović argues, ‘reflects the typist’s record on the gramophone in “The Fire Sermon”’ (4). Brooks compares lines in ‘Sybilline’ to Eliot’s poems ‘Preludes’, ‘A Game of Chess’ and ‘Prufrock’ (Clovis 100). For example, ‘The winter evening settles down’ (‘Preludes’) and ‘The evening / settles down’ (Malley). Such allusions contribute to the immediate ‘unveiling’ once the hoax is declared as performed ‘like a magic show’ (Fleming and O’Carroll 58).

Part of the humour of the Malley poems thus derives from the hints of fakery, seen in the pun ‘clews’ (i.e., clues), as the speaker in ‘Young Prince of Tyre’ is ‘hung up, dry, a fidgety ghost’ (53). ‘Dürer: Innsbruck, 1495’ introduces the idea of the ‘interloper’, while the ‘black swan of trespass on alien waters’ connects a sense of alienation to an ironic conversation, not only with European culture of old but also with contemporary modernism. Thus, the text embodies the sort of ‘cross-cultural appropriations’ Ramazani speaks about in ‘Modernist Bricolage, Postcolonial Hybridity’; Ern Malley emerges – to use Ramazani’s phrase – as one of modernism’s ‘postcolonial afterlives’ (460). After declaring that, ‘a poet may not exist’ in ‘Sybille’, Malley asserts, ‘And yet I shall be raised up / on the vertical banners of praise’ (39). In ‘Palinode’ (a form of ‘retraction’), Malley indicates that ‘these distractions were clues / To a transposed version / Of our too rigid state’ (44). This ‘rigid state’ might connote the dead (i.e., not-living) body of the poet, while the body of work is a ‘transposed version’ of something once alive (i.e., the postcolonial afterlife of another text). The lines also appear to echo Shakespeare’s Hamlet (Act 1, Scene 2), both in the reference to Hyperion (Hamlet struggles with his own sense of self), and the phrase ‘too rigid state’ (Malley) recalling ‘too solid flesh’ (Shakespeare). The last poem includes a clever image of emergence; sexual innuendo, and a play on words in the grammatical meaning of ‘infinitive’ and the Phoenix-rising this suggests. The thistle ‘Puffs its full seed upon the indicative air. / I have split the infinitive. Beyond is anything’ (61).

Ironically, the Ern Malley poems – long read as indicative of belated modernism – have themselves been subject to claims of being a derivative hoax. For example, James Crouch points to Cyril Connolly’s imaginary poet ‘John Weaver’ as the possible ‘direct model for Ern Malley’ in a literary hoax also involving Herbert Read in the November 1941 issue of the London literary journal Horizon (435). Other than the notion of Read as a target for comeuppance, evidence for Weaver as ‘a possible stimulus’ is circumstantial. David Brooks (1991) speculates on a parodic collection of symbolist poems by Henri Beauclair and Gabriel Vicaire, ‘Les Deliquescences d’Adore Floupette’ (Paris, 1885) as an ‘intriguing possibility’ of a French literary model. Connections include the biographical element, the ‘manifesto-like preface’, the shared age of death of the two fake-poets (twenty-five, like Keats), the similar number of poems, and the possibility that McAuley may have had access to a rare copy in Christopher Brennan’s library. Brook’s 2008 literary history The Sons of Clovis has been described as ‘a quest for evidence that the hoaxers knew of a previous hoax creation’ (Duwell 90). There is something unsettling in such investigations, suggesting as they do the notion of a ‘fake fake’, although it does mean reading Malley in a ‘Borgesian or Nabokovian light’, which David Lehman suggests is the right spirit (73).

A more ‘knowing’ emergent Australian modernism is argued by Melinda Cooper. Cooper reads Eleanor Dark’s novel, Prelude to Christopher (1934) as an example of 1930s Australian modernism that challenges the ‘cosmopolitan/nationalism binary’ of its reception (316). This argument supports Friedman’s concept of ‘mobile modernisms’, whereby the focus is on ‘interculturalism’ and a ‘network of texts’ (220–221). Concerning the Ern Malley hoax, Cooper writes, ‘[a]lthough such anti-modernist critiques were not unique to Australia, they have helped to construct a narrative that the nation largely resisted the arrival of literary and artistic modernism’ (317). Cooper demonstrates that the story of Australian modernism is more complex than this suggests; the anti-modernist editors of the Australian art magazine Vision (1923–1924), for example, ‘knew their modernism better than anyone else in the country’ (Carter, 85–98, qtd in Cooper 318). Similarly, McAuley and Stewart’s ‘attempt to discredit literary modernism relied upon a strong understanding of surrealism and Dadaist experimentation’ (Cooper 318). To extend Cooper’s argument, even if their intentions were parodic, the two poets also demonstrated a sophisticated understanding of a proximate response to world events in ‘Petit Testament’:

And in the magazines I have read

The Popular Front-to-Back.

But where I have lived

Spain weeps into the gutters of Footscray

Guernica is the ticking of the clock

The nightmare has become real, not as belief

But in the scrub-typhus of Mubo. (61)

Here the play on words, ‘Popular Front-to-Back’, references the Popular Front of the Spanish Republic (the pact signed by the various left-wing political organisations), also a phenomenon in France in the 1930s. The implied left-wing sympathy, given the defeat of the Republic, in ‘Spain weeps into the gutters of Footscray,’ is a possible clue to the publisher of Angry Penguins, since – as already mentioned – Max Harris’s poem ‘Progress of Defeat’ concerns ‘the traumas of that conflict’ (Heyward 26), while Footscray was a working-class suburb in Melbourne. The line ‘Guernica is the ticking of the clock’ could be read as a serious (retrospective) warning about fascism, indicative of a concern with a global problem.

The cultural significance of The Darkening Ecliptic – beyond its initial and often repeated reflection of ‘belated’ modernism – has been the subject of recent scholarship, in its original form, in the visual arts, and in response to its fictional appropriation in Peter Carey’s My Life as a Fake (2003). In ‘The Eternal Ern’, John McDonald describes Garry Shead’s Ern Malley paintings as ‘the most substantial works of Shead’s long career’ (65), while Sue Roff’s essay ‘Ern and Ned, Sun and Sid’ traces artist Sidney Nolan’s place in the hoax and relays Nolan’s own intriguing statement: ‘[w]ithout Ern there would have been no Ned’ (199).5 In their introduction to a special edition of Australian Literary Studies in 2004, Maggie Nolan and Carrie Dawson contextualise Ern Malley in a wider investigation into a range of historical and present literary hoaxes, and ‘identity crises’ (vii). In the Australian context, such hoaxes share ‘common and pressing concerns about the nature of authenticity and attendant fantasies of originary [sic] wholeness and certainty’ (xi). In the same publication, Bill Ashcroft argues that in My Life as a Fake, Carey makes Bob McCorkle ‘a surprising figure of colonial resistance’ (McCorkle is a Malley figure, come to life). Ashcroft re-reads the Malley lines, ‘Now I find that once more I have shrunk / To an interloper, robber of dead men’s dream’ in post-colonial terms: ‘The post-colonial poet is a “robber” of the dream of a dying culture, or at least of the dream of its dead exponents, a beautiful description of the literary canon’ (36). Such a reading of Malley suggests an ‘Eternal Ern’ – to use McDonald’s phrase – in which the work of two Australian poets function decades later as part of a conversation with international modernism (i.e., a ‘proximate reading’). Ashcroft sees in Carey’s appropriation of Malley ‘[a] literary truth … created anew out of old materials – this is the story of post-colonial literatures’ (39). For Ashcroft, Carey’s ‘Malley’ is a figure of post-colonial defiance, writing back to the imperial centre (Ashcroft et al.)

The ongoing scholarship and cultural appropriation of the figure of Ern Malley constitutes the fascinating cultural ‘afterlife’ of the text. Juxtaposing Malley with Max Aub’s Jusep Torres Campalans sheds new light on writers from ‘different nodal points of modernity’ (Friedman ‘Paranoia’ 245–246; qtd. in Gelder 11). A tangential connection to the Spanish Civil War is a relational starting point. Campalans is a Catalan anarchist exile, while the name of the journal ‘The Angry Penguins’ (the target of the Ern Malley hoax) comes from Harris’s poem about the Spanish Civil War, ‘Progress of Defeat’ (Heywood 26). As noted, ‘Malley’ references the Spanish Civil War in ‘Petit Testament’, while Aub references the Australian miners’ strike of 1912 in the annals section of Jusep Torres Campalans – a semantic ‘criss-cross’. More centrally, both hoaxes invent artists who might contribute something vital to the history of European modernism if only the apocryphal modernists were accepted as such, and their talents acknowledged.

Jusep Torres Campalans

As an innovative writer, and as an ‘international Catalan’ exiled from Spain following the defeat of the Spanish Republic in 1939, Max Aub embodies many aspects of transnational modernism. As with Gelder’s discussion of the Australian/Vietnamese writer Nam Le, Aub’s ‘proximate’ relationship to ‘home’ is a complex one. Born in Paris in 1903 to a German father and a French mother, Aub’s family moved to Spain at the outbreak of the First World War, where he lived for the next twenty-five years. Coming of age in ‘avant-garde circles’ of late 1920s Barcelona, Aub was committed to modernist experimental prose, and mentored by José Ortega y Gasset who believed in a ‘dehumanized art’, including abstraction in the plastic arts (Faber 237–238; Linhard 219). In the 1930s, Aub turned towards a more politically engaged style, ‘a specific brand of critical realism’ (Faber 238). He served the Republic government as a cultural attaché in Paris, where he commissioned works by Miró, Picasso and Alberto Sanchéz for the 1937 Paris International Exhibition (Gesser 39). Following the Nationalists’ victory in 1939, Aub was arrested in France in 1940 and transferred to prison in Algeria. From there he escaped to Mexico where he lived until his death in 1972. Aub was thus a cosmopolitan writer whose decision to write in Spanish rather than French or English, away from Spain, marginalised him in complex ways. In Mexico, ‘he was looked upon as a Spaniard’ (Faber 221). Yet during the Franco period, which extended until after Aub’s death, he was ‘erased from public consciousness in Spain’ and ‘unknown in literary capitals like Paris, [where] exiled writers seem to have the wrong language, the wrong approach, or the wrong purpose’ (Berman 192, qtd. in Linhard 218).

In Planetary Modernisms, Susan Stanford Friedman writes about ‘four modes of reading modernism planetarily’, including ‘collaging modernisms in different times and places for the insight radical juxtapositions can make’ (11). Referencing Friedman’s approach, Gelder writes that ‘parataxis [meaning ‘alongside’] is effectively a way of re-engaging with the issue of proximity’ (11). Here a hoax poet from 1940s Australia is juxtaposed to a 1950s fake artist, presented to the world as a significant painter within a ‘fully documented biography’ (Jusep Torres Campalans). As Katsoulis has noted of the various hoaxers in her study, ‘… one thing [hoaxers] nearly all have in common is that they are writing from the margins’ (3). As a projected figure from an exiled writer, Campalans the artist is somewhat like Malley the poet: both are isolated modernists. However, while Malley is ‘undiscovered’ until Harris is presented with The Darkening Ecliptic of the deceased poet, Campalans is a ‘neglected artist’ living far from his Catalan homeland, ripe for ‘rediscovery’.

Max Aub’s magnum opus was El laberinto mágico, a six-volume chronicle of the Spanish Civil War (1939 to 1968). The Magic Labyrinth blurs generic boundaries, since it is presented as fiction and yet ‘historical figures …outnumber fictional ones’ (Faber 238). Jusep Torres Campalans mixes genres more intentionally, including narrative, personal diary, critical essays, and an exhibition catalogue, all formulated as an ‘historical masquerade’ (Rosell 139). Rosell connects Aub’s work to Spanish ‘apocryphal and heteronymous authors’ who share the three characteristics of ‘experimentation, general hybridity, and intermittent composition – particularly when creating a literary heteronym’ (130). Aguirre-Oteiza writes that Aub’s ‘testimonial tropes’ are ‘the alias and the apocryphal’, reflected in the fact that the Campalans has at times been listed as the biography of a real painter (9–10). The back flap provides a strong clue as to its true form: ‘[Aub] brings Torres Campalans and the moral and intellectual history of his times to life as if in a picaresque novel’.

Aub’s earlier prose work Vida y obra de Luis Alvarez Petreña (1934) concerned a ‘supposed real intellectual pseudo-romantic’ (Rosell 138). Faber describes this text as ‘an apocryphal biography of a failed avant-garde poet’ (238). In a self-referential manner, Petreña’s fictional birth is included in the Annals section of Jusep Torres Campalans (37). In Campalans, Aub builds on his earlier work, executing what Faber describes as ‘an exceptionally well-orchestrated literary hoax’ (237). The publication of the Spanish, English and French language editions were supported by exhibits of ‘Campalan’ canvases (done by Aub) in credible galleries in Mexico City, Paris and New York between 1958 and 1962 (Rosell 140; Gesser 42) – the discoverable ‘prank’ elements. Prominent Mexican writers Octavio Paz and Carlos Fuentes assisted the hoax by praising Aub for his work in recovering a painter central to the history of Cubism. Camplans paintings exhibited at the Galería Excelsior in Mexico City in July 1958 impressed critics, with ‘[n]umerous press releases … published, praising the artist and congratulating Aub on taking this initiative’ without suspecting the fakery (Marzo 10). While the hoax was soon revealed in Mexico, newspaper articles from the time of its English translation in 1962 demonstrate ongoing confusion. The New York exhibition of the paintings was accompanied by a Boston Globe headline ‘It will be trick AND treat at a prominent New York Gallery Monday’, while ‘Campalans’ even appeared in London’s Evening Standard in the entertainment section.6 Apart from the gallery exhibits, Jusep Torres Campalans presents ‘real’ evidence of the painter’s existence, with the ‘first-hand’ sources of Campalan’s Green Notebook, and Aub’s own interview with Campalans. The Annals section includes a Tate Gallery catalogue, and short academic essays, the first of which is ‘A Founder of Cubism: Jusep Torres Campalans’ (Aub 127).

The reading strategy of juxtaposing texts from different times and places sheds ‘new light [through] geopolitical conjecture’, recognising both ‘heterogeneity’ as well as ‘reciprocal influences and cultural mimesis’ (Friedman ‘Paranoia’ 245–246, qtd. in Gelder 11). Differences as well as similarities, in other words, hold significance in parataxis. In the Australian context, the fallout of the Ern Malley hoax included a censorship trial and ongoing controversies based on ‘deep differences in aesthetic ideology’ (Mead 2). In contrast, while the revelations about Campalans as hoax may have disappointed some, it did not stop Aub from continuing to make use of the heteronym. In 1964 ‘Campalans’ illustrated 104 playing cards that form a fragmented novel when pieced together by means of text written on one side of the cards (Rosell 142). Arguments about the cultural significance of Campalans is where ‘deep differences’ (proximate divergences) emerge, however, stemming from Aub’s status as a political exile at the time of writing (Faber 244). A 2003 exhibition and catalogue of Campalans at the Reina Sofa (Madrid), for example, was criticised for emphasising the ‘humorous, mischievous’ elements of the hoax over its ‘incisive political critique’ (Gesser 40–41). Faber connects the falsehoods of the text to a commentary on Francoism, constituting ‘a rare sample of … politically committed, realist postmodernism’ (245). Such interpretations emphasise Aub’s weighty purpose, lest ‘institutional efforts … neutralise the subversive potential of his writings’ (Aguiree-Oteiza 14). Here Campalans is read not only as artistic parody, but as an authentic text exposing both the lies of Francoism and the arrogance of the Spanish left ‘before, during and after the War’ (Gesser 45). In contrast, while the poets behind The Darkening Ecliptic had intended their hoax as ‘a serious literary experiment’, it has not always been treated as such. Ashcroft’s reading of ‘Malley’ through Carey’s My Life as a Fake is an example of a more profound appreciation of the ‘culturally disruptive and resistant’ nature of the text (31); the pairing of Malley with Campalans here is an attempt to strengthen the case by juxtaposition of two modernist hoax creations from the margins.

While Campalans is ‘organised as a puzzle surrounding the figure of the protagonist,’ it is also ‘nourished by heterogeneous sources’ (Rosell 141). This approach not only confers originality but also allows the text to function as a ‘decomposition’ (15) – or deconstruction – of the art monograph form it inhabits.7 Aub serves as both narrator and character in the text and author of the text, seen in the fact that Aub-as-character is a European visiting Mexico, whereas Aub-as-writer lived in Mexico in permanent exile. Here Aub demonstrates a playfulness with proximity in situating the present action in a ‘non-cosmopolitan’ (Gelder 8) setting. On the first page of the prologue, Aub describes his arrival in the state of Chiapas to deliver a lecture on Don Quixote where he is introduced to a ‘dry sort of man referred to as “Don Jusepe”’ (14). Aub notices that the artist is Catalan (an important element of the biography) but withholds the ‘two conversations’ until ‘their proper place’ (i.e., Part VI). As narrator, Aub then jumps forward to 1957 (‘Last year – 1956…’) and recounts a conversation with real-life French writer and intellectual, Jean Cassou, who supplies Aub with a Tate Gallery catalogue of Campalans’ paintings written by a certain Henry Richard Town (conveniently killed in the Blitz). The ‘Indispensable Prologue’ thus serves two purposes, both linked in the narrative art of biography. First, the prologue sets up the mystery of the lost artist. Second, Aub justifies his unorthodox approach, in which he treats the life, the works, statements, articles and conversations separately:

This, then, a ‘de-composition,’ with the biography appearing from several points of view – perhaps, unintentionally, in the style of a cubist painting. (15)

Aub’s playfulness with genre is signalled again when he writes, ‘[w]riting a biography is a trap for a novelist who doubles as a playwright’ (15). Don Quixote (echoed in ‘Don Jusepe’) is referenced a second time as Aub makes the point that biographies of painters are popular today, just as in Cervantes’ time ‘they read books about Amadis of Gaul’8 – one of many literary citations in the work.

In ‘Malley’, James McAuley and Harold Stewart suggest cultural provincialism in their phrase ‘Australian outcrop of literary fashion’ (12]. In Campalans, the Acknowledgements concludes with the Aub narrator ‘waiting in vain’ for Picasso – surely the critical interviewee to prove the importance of Campalans as a provincial artist – while Aub the novelist supplies the narrative hook in the last sentence: ‘He disappeared without leaving a trace. He had talent’ (22). Such foretelling is effective in this apocryphal biography, since narrative is ‘common to both historical and fictional writing’, and biography is a ‘hybrid genre that is grounded in history but shares many of the characteristics of fiction’ (Benton 68).

The Annals section offers an ‘illusionary precision’ suggesting a parody of chronological overviews seen in typical ‘Life and Works’ monographs (Faber 239). However, a political dimension is at work here too. Three motifs emerge from the ‘events’ collated in the Annals. The first is a progressive politics, relaying the history of basic working conditions over time in different countries. For example, the raising of the working age of children in England to eleven in 1901 (46), the eight-hour day for miners in France in 1905 (50) and, as noted earlier, the Australian miners’ strike of 1912 (61). A second motif reflects a bias in favour of Catalan national identity, and the inherent political complications this brings given the ‘internationalist’ mindset the Annals otherwise espouse. For example, in 1892 the ‘Uníon Catalanista’ held a General Assembly at the Catalan stronghold of Manresa (32). The foundation of the cabaret ‘Els IV Gats’ – of Catalan cultural significance – is subtly included as an ‘event’ rather than under the heading of ‘Fine Arts’. The third motif is the condemnation of colonialism, indicated in the matter-of-fact tone used in listing monumental actions by the ‘Great Powers’ in the lead up to WW1. For example, the division of Nigeria by France and Spain in 1890 (30), France’s 1895 conquest of Tonkin and Madagascar (35), the ‘Anglo-German-United States convention’ deciding the fate of the Samoan Islands, and – less subtly – the off-hand brutality implied by ‘[t]he Maxim Company tries out its machine gun in a Hindu village called Dumdum’ (1899, [44–45]).

As these three interrelated motifs suggest – the listings demonstrate engagement in the fields of both modernism and post-colonialism (key events in literature, theatre and fine arts are almost entirely modernist, or related to modernity). This is comparable to the ‘culturally disruptive’ nature of Malley (Ashcroft 31) in signalling a rival account of modernism. In the Fine Arts listings, a narrative around Cubism emerges, including the four ‘big names’ in Cubism coming together in 1910: ‘Leger meets Picasso, Braque, and Campalans’ (58). In Part 4, positioning Campalans as a Catalan exiled in provincial Mexico, living with Indigenous people away from the capital of Chiapas, further challenges existing hierarchies about modernism in the plastic arts. Aub’s ‘failure’ to capture the essence of the disappeared artist can be read as a critique of the tendency of European modernists, to use Ramazani’s phrase, to be ‘problematically appropriative’ (457). That is, Aub’s claim to ‘decompose’ a text is ironic. As narrator, Aub-the-character leaves Mexico with the authority of a European reclaiming a Catalan/Mexican subject while Aub-the-writer continued to live as a Catalan in exile until his dying days.

Biographies are said to simplify a subject, since it is ‘self-evident’ that the ‘biographical narrative cannot capture all that lies behind it’ (Benton 6). Aub refuses such simplification, asking rhetorically, ‘[h]ow much can we know about another human being – know precisely – unless we convert him into an actual character?’ His solution is to ‘set apart’ the artworks from Campalan’s writings, the articles about his work, and the conversations the author has with the artist (15). Unlike typical art monographs, the collection of artworks in Campalans is confined to a reproduction of an (invented) Tate Gallery catalogue, with plates and descriptions from a proposed 1942 exhibition. These simple ‘artworks’ belie the supposed genius behind them, as we see in Plate XVI.

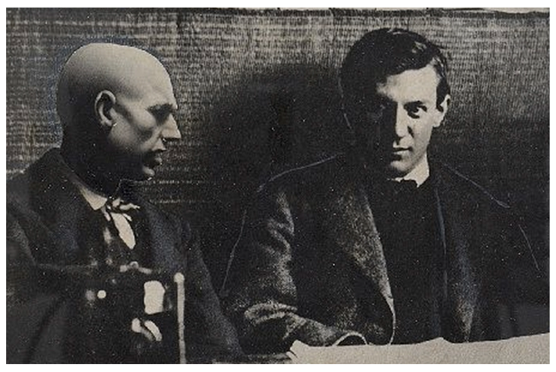

Descriptions of other paintings in the catalogue suggest outright fakery, for example, ‘Red Landscape’ is summarised as ‘Gouache on cardboard. Despite the signature, I doubt its authenticity’ (118). Some cartoon-like ink drawings are included in the ‘Biography’ section of the novel, while one hoax photograph presents Picasso and Campalans together, supposedly taken by José Renau in 1902 (144), as well as comically stereotypical photographs of the artist’s father and mother, peasants from Bellpuig in Catalunya (139).

A key difference emerges in the ‘art’ produced as part of the two hoaxes. Whereas the visual hoax elements of Campalan’s ‘art’ appear underwhelming, the Malley poems are not so easily dismissed; as Chambers writes, while intended as a fake, the poetry ‘turned out to be not easily distinguished from genuine poesis in the modernist mode’ (34). However, Campalans functions as a largely literary text, and like Malley, Campalans has been described in terms of his existence beyond the life of the hoax:

Jusep Torres Campalans forms an illustrious part of a double genealogy, literary and artistic: that of non-existent, apocryphal or heteronymous authors and that of the phantoms of art who have ultimately become faithful reflections in their own right of the history of culture and its paradoxes. (Marzo, Section 10)9

As Faber notes, both the biography and notebook end in 1914, as ‘a moment of severe crisis in the painter’s life’ (240). The ‘San Crisóbal Conversations’ document Aub’s meeting the reclusive artist, and the nature of their conversations in 1956. (Campalans is an old man, recalling the days of his youth). The text thus largely bypasses the events of the 1930s and the Spanish Civil War (the focus of the Magical Labyrinth series), though Campalans has a few significant things to say about Catalanism and anarchism in the conclusion to Part 6, causes critical to understanding the Civil War.

Like the convenient death of the author of the catalogue of Campalan’s paintings in Part III, Part IV (Biography) begins with a fundamental yet unprovable ‘fact’:

As was proved by the parish register of San Esteban, which was burned in 1936, Jusep Torres Campalans was born on September 2, 1886, in Mollerusa. Jean Cassou gave me this information which was on page 17 of the date for that year. (137, my emphasis).

Such tomfoolery (‘as was proved … which was burned’) exemplifies the ‘mock hoax’ in the ‘conscious tricks’ it plays with authorship (Katsoulis 4). The seriousness of the hoax is evident in complex ways, however, including its avoidance of the Franco period in its focus on the artist as a young man (up to 1914) and in old age (1956). Faber argues that Aub’s Campalans provides an ‘ironic commentary of the web of official lies that sustain a totalitarian regime … where texts – paper, records, files – assume the place of reality’. As Aub was a political exile, ‘his life and works were practically erased from Francoist Spain,’ and what information remained was ‘distorted beyond recognition’ (244). Here, the burned register – with a specific page reference to a non-existent document – acts as a metonym for the instability of reality, both within and outside of corrupt official records. While in his earlier statement of methodology in Part I Aub states that he wishes to ‘stick to the truth’ and ‘describe the living body’ (where documents are ‘like the pins used to hold back the skin of a cadaver while dissecting it’ [15]), the biography section is full of unverifiable information. Fleming and O’Carroll discuss the hoax as ‘Derridean double writing’ where the hoaxer writes an event ‘that resembles the original, but has, within it in palimpsestic fashion, another text, one that frames, and yet is contained by the main text’ (48). Aub’s ‘de-composition’ does not simply serve the creation of a Cubist portrait/biography (15), but highlights the deconstructive potential of the literary hoax, resembling an art biography, but full of notes in the margin of the ‘historical’ record.

Narrative elements in the Biography section provide subtle comedy when one considers the traditional dichotomy between the novelist who ‘constructs a narrative of imagined events,’ and the historian (biographer) ‘[who] reconstructs a narrative from real-life past events’ (Benton 69). Aub writes the narrative in omniscient style, with Campalan’s thoughts reported directly. For example, Aub reports that in Barcelona, Campalans stumbles on the Escuela de Bellas Arts and meets a professor from the school and his son, Pablo Ruiz (i.e., a young Picasso). Hearing that Campalans is a virgin, Picasso takes Campalans to a brothel in the Calle de Aviño, and Aub brilliantly uses an unverifiable claim to indicate the ultimate results of this personal event, involving – as in the painting – ‘five girls’ – a very significant citation, a key element of Gelder’s proximate reading (here Campalans is literally beside the key modernist painter of the twentieth century):

In 1906, when Jusep Torres again met Pablo Ruiz in Paris, they went to a bistro. There they recalled those events, which by then seems to belong to a remote past. The result was one of the most famous paintings in modern art, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. (143)

Apart from such playfulness with the events of history, Aub characterises Campalans as a strong-willed individual who for a time was an enthusiastic anarchist whose painting career was encouraged by a freight manager at the Gerona railway station, ‘a devoted Anarchist and an intense admirer of the Catalan poet Jacinto Verdaguer’ (156). This man, Domingo Foix, encourages Campalans to think for himself, until the pair fall into a political disagreement (Campalans maintains his Catholic faith) and Foix tears up all the young artist’s sketches to this point (162), thus destroying important documentation of the biographical subject. Aub continues his portrayal of Campalans as a man of complex beliefs by describing his later disagreements in Paris with countryman (and real-life cubist) Juan Gris, with whom ‘the natural Catalan-Castilian enmity was at play’ (200). Here a detailed argument is included via a fictional source (Berthe Ratibor Ternichewski, [footnote 201]). Such sequences characterise Campalan’s passionate Catalan identity, insulting Gris’s Madrid accent, for example. Ultimately Aub draws Campalans’ beliefs into crisis as the war looms in 1914, and the artist realises that the patriotic workers of France and Germany will kill each other. As he voices these concerns, Campalan’s enemy Plá equates Catalanism to French nationalism (‘Vive la France!’ is answered ironically by ‘Vixca Catalunya lliure!’). Campalans argues for a nobler form of Catalanism:

That’s something else. It never occurred to us to declare war on the Aragonese. But these Frenchmen dream only of dis-emboweling [sic] the boches simply because they’re German and speak German. (216)

While the conversation here is meant to represent Campalans’s crisis of 1914 – he leaves France for Mexico to avoid the war – Aub is all too aware that while the Catalans might not declare war on the Aragonese, all regions of Spain would be caught up in a bloody civil war after the Nationalist coup in June 1936. To return to Malley’s lament in ‘Petit Testament’, ‘Spain weeps in the gutters of Footscray … The nightmare has become real …. (‘Malley’ 61)

Just as McAuley and Harold Stewart parody forms of modernist poetry, Aub’s playful ‘decomposition’ of the biographical form challenges other accounts of Cubism by ‘showing the workings’ of a writer self-consciously constructing an ‘historical’ figure. In choosing to write about an anarchist Catalan exiled in Mexico, Aub asks searching moral questions about the relationship between art and politics – questions which not only resonate on the period leading up to the Great War, but on the turmoil of the 1930s, and the post-war setting of the novel’s present tense (1956–1957) as Aub writes and ‘publishes’ his apocryphal biography.

Conclusion

In this essay I have paired two apocryphal modernists from the 1944 and 1958 – a ‘deceased’ Australian poet and a ‘disappeared’ Catalan painter – brought to life in literary hoaxes by James McAuley and Harold Stewart (The Darkening Ecliptic) and Max Aub (Jusep Torres Campalans). Friedman defines parataxis as ‘a common aesthetic strategy in modernist writing and art, developed to disrupt and fragment conventional sequencing…’ and as, ‘the juxtaposition of things without providing connectives’ (21). Gelder pairs a theory of ‘proximate reading’ to Friedman’s parataxis, reading texts ‘alongside’ one another and thereby ‘re-engaging with the issue of proximity, providing a “criss-crossing set of pathways” that may also … not criss-cross at all’ (11). Here the literary hoax has been presented as an example of a ‘transnational semantic network’ (4) which allows for a degree of ‘in/commensurability’ of two texts ‘set in conversation’ (Friedman 281). Writing in 2008, Mead asks, ‘What would further critical and comparative studies of Australian fakemeisters reveal? (91). To this can be added a question posed in Spain by Rosell: what artistic qualities emerge if ‘apocryphal literature itself can be considered as an independent canon’? (150)

Katsoulis notes that ‘one thing [hoaxers] nearly all have in common is that they are writing from the margins’ (3). Jusep Torres Campalans is recognised as such when included in the opening chapter of a study of Hispanic literature, Modernism and its Margins. Aguinaga notes that ‘Max Aub’s decentering of modernism is an exemplary cultural lesson’ through its tongue-in-cheek, implicit proposal of ‘a pluricultural modernist canon (qtd. in Geist & Monleón 12–13). The critical concern addressed ‘should be obvious to everyone’: hegemonic culture ‘appropriates and excludes whatever it needs from the periphery’ (15). Aguinaga’s characterisation of the challenge to such hegemony presented by Jusep Torres Campalans can be compared to Bill Ashcroft’s reading of Peter Carey’s My Life as a Fake which ‘sees Ern Malley as a specifically Australian voice, disrupting the canonical truths of European culture’ (28) – and in so doing, strengthen both claims.

Both ‘Malley’ and Campalans challenge the canon with their creation of unique, peripheral modernists. Jusep Torres Campalans (as a figure) emerges strongly from within a text that undermines his stability –as if the biography cannot quite capture the reality of the shadowy man – giving him a foothold in the world. In the preface to The Darkening Ecliptic, Malley writes that ‘[e]very poem should be an autarky’ (30) – a claim that could be read as a utopian dream of cultural independence, just as a proximate reading might highlight the playful meanings found in Malley’s speculation that ‘… the world is a mental occurrence [where] a point-to-point relation is no longer genuine …’ (31). Campalan’s ‘Green Notebook’ is full of strongly worded artistic claims and speculations (‘Art burns or it does not exist’ [Aub 229]; ‘Stick a bomb into the subject and detonate it. Then paint from any angle whatever’ [236]; ‘To paint is to capture’ [263]). The two created artists share a desire to work on their own terms, though fated for obscurity, ‘conjure[d] up’ – as Carey puts it, as one ‘without the protection of the world that comes from living in it. A man outside’ (279).

Gelder concludes that ‘…proximate reading is about distance as much as proximity, about the ways in which being proximate to one thing can mean being remote from another’ (11). When read side-by-side, The Darkening Ecliptic and Jusep Torres Campalans serve as comparable examples of ‘post-colonial modernism’ in highlighting their deconstructive hoax elements. The young poets in McAuley and Stewart write at a distance from the Anglo-American modernist culture they parody, and yet they do so with a literary knowledge, engaging closely with European poetry in the form of proximate citations. Max Aub’s distance from European modernism via political exile does not mean he is entirely remote from the transnational tissues linking the arts across the seas, as he invents a reclusive artist living among the Indigenous people of Chiapas, and a narrator who bears his name: a visiting, intellectual Spaniard. The front flap of Jusep Torres Campalans includes the claim that ‘[t]he rediscovery of Torres Campalans makes possible a fresh view of this [modernist] period’. A ‘relational view’ (Friedman) extends the ‘rediscovery’ of Campalans to a ‘review’ of Malley. In this manner, renewed significance can be explored in their invented art and biographies. In the final analysis, both texts portray a certain yearning for significance. In Malley’s words – ‘a dream of recognition’ (47).

Footnotes

-

Page references are to the 1962 Doubleday & Company edition. Australian readers can request a copy through the National Library of Australia (https://catalogue.nla.gov.au/catalog/2508070). The novel has been republished periodically in Spanish, English, French and Italian, as recently as 2021 (French edition, Verticales).

↩ -

The Ern Malley trial is a fascinating topic beyond the scope of this paper, explored in depth in Philip Mead’s Networked Language. Culture and History in Australian Poetry (2008) and Michael Heyward’s The Ern Malley Affair (1993).

↩ -

Max Aub’s place in world literature is complicated by his exile in Mexico, following the defeat of the Spanish Republic in 1939 (Spanish Civil War). Jusep Torres Campalans is the ‘biography’ of a Catalan artist in exile.

↩ -

The page references to ‘Malley’ refer to the 2017 ETT Imprint, first published in 1993 by Angus & Robertson.

↩ -

The argument relates to Sidney Nolan’s desertion from the army in 1944, and his painting of Ned Kelly in the Wimmera district while an ‘outlaw’ himself, living under the false name, Robin Murray (Roff 199).

↩ -

International references to the Campalans hoax include New York Times, 28 October 1962 (‘Artist Campalans’); Boston Sunday Globe, 28 October 1962 (‘Trick and Treat at N.Y. Gallery: Exhibit to Feature Paintings by Artist Who Never Existed’), and London’s Evening Standard, 24 February 1961 (‘Hoaxer’).

↩ -

Aub’s desconstruction of the art biography is signalled in the organisation of Jusep Torres Campalans, divided as it is into six sections: I Indispensable Prologue, II Acknowledgements, III Annals, IV Biography, V Green Notebook, and VI San Cristóbal Conversations. Part I and Part VI serve as bookends to the ‘biography’ by positioning the reader as witness to Aub’s two meetings with the disappeared artist.

↩ -

The reference to Amadis of Gaul is suggestive of the unreliable nature of the art memoir, since its origins as a chivalric romance are unknown (‘Amadis of Gaul’).

↩ -

Here the Valencia ‘Fake’ exhibition catalogue compares Campalans to such figures as Pavel Jerdanowitch (1924) invented by Paul Jordan-Smith; Bruno Hat (1929), created by Brian Howard; and Hank Herron (1973), brought to life by Carol Duncan.

↩