Michelle Grossman’s 1998 overview of Australian Indigenous women’s writing identified significant contributions to the country’s literatures, particularly through women’s life writing. This form, Grossman claimed

sits most comfortably in the hands and on the pages of a certain generation of Indigenous women writers, those old enough and experienced enough to have the capacity and resources to reflect upon, structure and narrativise rich and complex personal/collective histories. (176)

For some of these writers, political imperatives to create spaces for alternative versions of history to those promulgated by the white dominant culture called for the kind of truth-telling that comes from ‘telling it how it is’. Ruby Langford Ginibi, for instance, remarked that ‘I’m not interested in fiction … because I’m too busy writing the truth about my people’ (Little 109). But Grossman also cites feminist critique warning against a simplified reading of women’s life writing that overlooks the ways in which it is ‘just as complex, just as constructionist, and just as productively unsettled by the disjuncts between textual and metatextual subject positions as other genres of literary representation’ (176). Brewster, O'Neill and van den Berg further claim that the generic boundaries between texts by Aboriginal writers (such as life story and fiction) were often blurred (10), a sentiment echoed by speculative fiction writer Ambelin Kwaymullina, who claims that ‘Indigenous narratives rarely fit neatly into Western genre divisions’ (26), and scholar and poet Jeanine Leane, who dismisses western generic boundaries as too reductive for some Indigenous texts (Kadmos 217). Grossman goes on to question: ‘How are younger Australian Indigenous women writers able to intervene in and work with this form?’ (176). This article recognises that among contemporary Aboriginal women writers, short stories, often drawing on personal and family histories filtered through contemporary narrative practices, feature strongly: as stand-alone pieces, in collections, and as parts of short story cycles, such as those by Tara June Winch, Gayle Kennedy and Marie Munkara. These latter texts, as collections of independent yet interconnected stories, affirm James Nagel’s claim that the short story cycle, through its interconnectedness of component parts, is popular with writers who wish to explore issues of ethnicity and identity formation and ‘the complexities of formulating a sense of self’ (15).

Mununjali woman Ellen van Neerven’s award-winning collection of stories, Heat and Light (2014), features a section of linked stories and thus confirms in part, Nagel’s assertion. The work can also be viewed as part of the re-emergence of the short story cycle in Australian literature where it appears to be popular with writers of varied cultural backgrounds, including Patrick Cullen, Gretchen Shirm and Luke Carmen. In this sense Neerven’s work might align as strongly with the preoccupations of her generational, as it does her cultural, peers. But as a whole the text resists easy categorisation, as a short story cycle or other form, offering rather an array of characters and circumstances in stories that are structured and narrated in radically differently ways throughout, as this article will show. Heat and Light demonstrates a nimbleness on the part of one young Aboriginal woman in the twenty-first century reworking, and working beyond, the tradition of Aboriginal women’s life writing, and exemplifies the ways that Indigenous voices in a range of discourses push against the boundaries within which they are often placed.1

This is not to say that Heat and Light does not draw from the author’s own life and experiences. Neerven comments that story ‘is informed by my cultural heritage, how I see narrative from my identity; it is ways of being, ways of transferring knowledge’. Different forms of story-telling are used in this book: Neerven adds that ‘to talk about Heat and Light you must talk about the form’. The text has a tripartite structure each part of which works differently to convey knowledge in the sense that Neerven uses it, representing an important aspect of her politicised sense of history and culture. ‘Heat’, a short story cycle of five interlinked stories, is the past; ‘Water’, a section comprising one long story, is the future; ‘Light’, a traditional collection of short stories, is Queensland, the author’s home state, in the present. The sixteen stories within the whole collection share a strong sense of place, though not a singular one, and explore some themes which might be seen as bedrocks of Aboriginal women’s writing such as the importance of extended family and the recurring impacts of family history on future generations, the pervasive experience of racial stereotyping and prejudice, and the adaptability and flexibility Aboriginal people must exercise to effectively straddle dual and sometimes multiple experiences of belonging. Yet the collection is also inflected by a contemporaneousness born of distinctly current concerns. Jessica Gildersleeve suggests that ‘the use of a young, female, queer narrator … a kind of lost, wandering women’ across several stories is ‘emblematic perhaps of a broader sense of displacement in contemporary Indigenous youth’ (102). I would extend this to Australian youth more broadly, where the representations seen in Heat and Light of different ages, genders, sexual orientations, ethnicities and family groupings in many ways reflect preoccupations of the author’s generation with the fluid aspects of intersectional identities. Different language groups are mentioned, including Bundjalung, and the stories occur in a wide range of recognisable geographical locations – urban and rural – predominantly up, down and inland from the Eastern coast but also northern Western Australia, representing the movement of many individuals and families for a variety of economic, spiritual and social reasons. As one character, Amy, says: ‘The usual reason I go down the highway to ancestral country is to go surfing, not to meet family or do any of the usual practices you’d expect me to do’ (6), a comment that, directed as it is to the reader, toys with the notion of ‘connection to country’, a concept that is as relational as it is spatial (Heiss 3). Here Amy asserts that she knows exactly where her country is and what it means to her, but that her relationship to country might be larger than both Indigenous and non-Indigenous readers might expect.

Neerven’s storytelling is diverse in its preoccupation and style. In addition to its varied structure, the text interweaves storytelling, realist, magic realist, gothic and speculative traditions, and these multiple layers significantly increase the text’s capacity to represent diversity beyond what might be possible in one form alone, such as life writing or conventional story collections. Further, the text eschews a central protagonist thus resisting the constraints that a more focalised point of view might impose. This is not uncommon in Aboriginal writing which is often less autocentric than much canonical western life writing and fiction which, according to Leane, ‘still mainly views identity construction in terms of the Enlightenment concept of the individualist’ (107). This polyphonous approach thus dramatises the notion of intersectional identities to reflect contemporary questions around ethnicity, sexuality and gender. For instance, the ways that Heat and Light eludes being categorised as one thing or another suggests the possibility of being ‘that, and more’, a sentiment expressed by some leaders and artists who resist the often-reductive inferences made about Indigenous people, such as author and social commentator Anita Heiss who says that ‘I’ve often felt that my life is about making others understand that you can’t prescribe Aboriginality, and you can’t place genetically based stereotypes on individuals’ (253). While similar concerns are reflected in a variety of texts by contemporary writers, artists and film-makers, the remainder of this article, dealing with each of its three parts separately, demonstrates how Heat and Light explores these ideas in unique ways through deploying various structures, genres and styles, thereby reinforcing the idea that opportunities for human experience to be enriched by different perspectives and modalities offered by new generations of writers are vast.

As a Euro-Australian researcher I am sensitive to the knowledge that some problematic outcomes have arisen from research around Indigenous culture and therefore, like Brewster (Giving this Country xiv) and Gillian Polack (27) amongst others, I strive to invite participation into the research process. This essay is informed by two conversations with Neerven which took place in March 2017; one of these involved Jeanine Leane who has also worked with the short story cycle form (Purple Threads 2011). These conversations were tape recorded and, unless cited otherwise, comments made by Neerven, quoted or paraphrased in this article, are drawn from those conversations.2

‘Heat’: the short story cycle and fragmented time

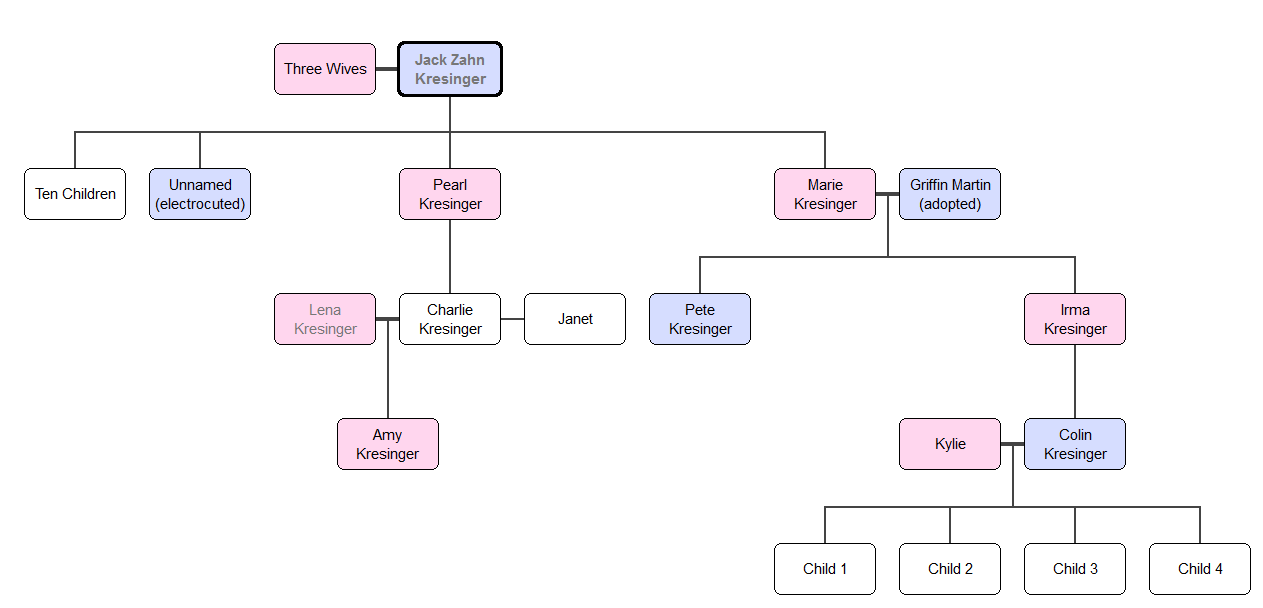

The notion of biography as collective record is synonymous with Aboriginal women’s life writing which is, as Eileen Moreton-Robinson says, ‘fundamentally social and relational, not something ascribed separately within the individual … [but] the collective memories of intergenerational relationships’ (1). Anita Heiss and Peter Minter extend this claim to Aboriginal writing in ‘essays, lectures and speeches’ too, which ‘remind us that Aboriginal literature remains grounded in the shared experiences of Aboriginal men and women’ (7). And Carole Ferrier remarks that many works of fiction by women writers also ‘trace the family histories of generations of Aboriginal people to better understand the present’ (19). In ‘Heat’ the short story cycle form achieves a powerful exploration of the impacts of family history on future generations because short cuts across time and space hone connections between people and events for maximum effect. While Amy, represented at different stages of her life, is established as a central character linking the past, present and future, the cycle mentions, at least briefly, members from five generations of the Kresinger family in just five stories (Figure 1). As Neerven explained, ‘it had to be multi-authored, because it is a family story ... it’s a family tree that’s been deconstructed. There’s no one Aboriginal person. I wanted to show as much diversity as I could’. Amy’s journey to self-awareness thus serves as a palimpsest, revealing and then concealing the stories of others. Leane remarks that the Aboriginal bildungsroman typically switches the focus from the individual to the community where ‘belonging and a sense of place are integral and essential’ (107) noting that Melissa Lucashenko’s Steam Pigs (1997) and Tara June Winch’s Swallow the Air (2006) exemplify this. Leane’s own collection of stories Purple Threads (2011) similarly contextualises protagonist Sunny’s journey within a larger story that includes her mother, aunties and Nan. Both belonging and place are privileged in ‘Heat’, where the setting of each story is integral to a particular character’s search for familial belonging.

Susan Garland Mann describes the defining feature of the short story cycle as the simultaneous independence and interrelatedness of the stories within it (15). When reading a cycle, the reader’s successive experience of engaging with the whole work modifies the experience of reading its component parts. Cycles thus often enable a rich picture of the complexity of relational identities, because the interrelatedness of the stories represent how individuals come to a greater sense of their personal and shared history through cumulative formative experiences involving themselves and others. When asked why she chose the short story cycle form in this instance, Neerven said ‘there’s a sense of completion’ about it, although ‘the spaces become very important. It’s tension, these pieces are pushing and pulling each other’. Interestingly, Mann has described this as a ‘necessary tension’ (17) which is ‘one of the chief pleasures that readers of cycles experience’ (19), a claim also supported by Neerven who remarked that the cycle is ‘intellectually stimulating’, a quality that people often ‘put enjoyment over, but that can mean the same thing’. Indeed, cycles enable readers to construct meaning through attention to the connections within and between the stories, and the silences (or what Neerven calls the ‘moments of stillness’). A brief look at each of the stories in ‘Heat’ shows how, through the successive reading of the stories, the connections and tensions in this mini cycle develop themes of identity and belonging, linking generations of the one family in specific temporal and geographical contexts, with each other and their shared and personal histories.

The first story, ‘Pearl’, straddles the past and present. Amy is twenty-six years old, and living with her father, Charlie. In a nod to traditional storytelling, the narrative opens with a stranger, an older woman, telling Amy about her past and the truth about her real grandmother, Pearl (sister of Marie, who Amy had always believed was her grandmother). The woman’s storytelling pulls Amy’s attention away from her contemporary urban life by connecting her to two previous generations of her family: to her great grandfather and respected elder, Zhany Zhany, and to free-spirited Pearl, his daughter, who cheated death more than once. By interweaving dual narratives – Amy’s own in the present and the old woman’s recount of Pearl in the past − the story explores the impact of family history on future lives. Through this, Amy, who is struggling with the implications of her own self-diagnosed sex addiction, recognises a wild and potentially dangerous impulse she shares with her grandmother: ‘I am like my grandmother Pearl. I am a strong black woman, and love comes too easy for me’ (8). Her father refuses to entertain a different version of his parentage, but Amy embraces the newly-found connection and frames it positively: ‘I think she was a fighter, I think there is a lot of struggle in our family and she has passed on that strength. I don’t know if she’s alive or dead, at peace or not, but I know she deserves to be a part of our family’s history’ (19).

The narrative time of ‘Heat’ is not linear – the stories jump back and forth in time. This irregular chronology is consistent with the short story cycle’s convention of juxtapositing disparate events and characters, focusing the reader’s attention on themes developing throughout (Hernáez Lerena 19). This play with chronological time allows greater emphasis on impact, and how experiences, including some that are shared, are felt and remembered differently by individuals. For Neerven, these possibilities opened up by the short story cycle form reflect ‘the way the retrospective looks, the unevenness of it’. We learn more about Amy and others and understand more about how each came to be who they are, by returning not just to the past, but to events involving other family members, which set off reverberations across generational lines. For instance, Amy and her cousin Colin, in different ways, reflect on their Aboriginal heritage and their belonging to family and country, but their need to question these connections arise from complex disruptions including inter-cultural marriage leading to dual-heritages, early parental death (an experience of several characters in the book as a whole) and the consequent loss of connection to one side of a family, geographic dislocation, social mobility and sexual diversity. Identity is also seen to be fluid and, in a contemporary context at least, deployed differently for specific reasons, as we see in the second story, ‘Soil’.

Set nearly twenty years after the events in ‘Pearl’, ‘Soil’ opens with Amy on holiday from her job at an Aboriginal organisation in Brisbane. Her father telephones, pleading with her to help her ‘brother-cousin’ (22) Colin, by supporting Colin’s application for something that is unspecified, but which the reader can presume is a letter of confirmation of Aboriginal identity that is commonly issued by Aboriginal organisations (Langton 29). Amy’s reluctance to agree outright is because Colin, who lives in Sydney with his white wife and four kids, ‘doesn’t identify’ and ‘probably just wanted to get the housing loan’ (22). The following passage captures the implications associated with the notion of having turned one’s back on one’s roots:

[Amy] didn’t use the terms that some of the others did, ‘coconut’, and so forth. She understood that it was easy for some of their mob to be white and project a whiteness. She imagined it was easy for them to live out their lives this way. And one day it might click, when they needed a job, a house, a surgery. Too easy. I’ll be black now. (22)

Amy ruminates on how little she’s seen of Colin since he ‘turned foul’ in his younger years (24) and stopped going back to visit their Nan. By the time Colin calls her himself, a few hours later, she has a response ready: ‘You come back up this way … you bring your family. You see the old mob, too … and we’ll see’ (26). Amy thus asserts the idea that belonging is a relational experience that is ongoing rather than static, but Colin’s reply reminds her, and the reader, that family histories, even shared experiences, leave unique impressions that force individualised responses. He says: ‘We have either succeeded or failed in getting over the horrors of our childhood’ (26).

A necessary preoccupation with much writing by Aboriginal people is the rupture to identity felt as a consequence of legislation that led to the Stolen Generations (Wheeler 6; Ferrier 27; Munkara Of Ashes). While identity and belonging are central themes in ‘Heat’ and the collection as a whole, little reference is made in these stories to the forced removal of children. For the most part, the central characters in Heat and Light grow up with their biological families, if not always with their parents. But this does not mean that the trauma of colonial policies and practices are resolved. Neerven affirmed that ‘there is still a processing of hurt and trauma that’s still going on.’ Non-Indigenous Australia can be blind to perpetual–intergenerational suffering, or reluctant to see and fully understand its complexities. As Brewster, O’Neill and van den Berg remark, ‘when Aboriginal people remember it is often what the dominant culture chooses to forget’ (13).

The ongoing impacts of the severance of cultural and family ties is one of the many aspects that the stories in Heat and Light explore from a contemporary perspective, and the third story, ‘Hot Stones’, is no exception. This story brings us deeper into Colin’s perspective through his first-person narration of a time when he was thirteen, ‘the age that makes you’ (27). We pick up very quickly that his feelings about his culture and heritage are complex, and vastly different from Amy’s dismissive assessment of them in the previous story. He reminisces that he ‘would sit eagerly by my grandmother’s side and wait for her yarnin’ time’ and recalls her words: ‘You are living and breathing on country. That makes you my very special grandson’ (27). And then he recounts a traumatic incident that would be difficult for any young person to come to terms with. A new Aboriginal girl, Mia, arrives at Colin’s school. She and Colin become close. Colin reminisces, ‘I’d say I was in love’ (29); when she visited him at home he ‘was in bliss having all my favourite people around me’ (30). But then Mia is raped by vengeful white youths, and it is Colin and Nana who find her. The incident traumatises Colin: ‘I thought about her dying every night. I couldn’t shake it. As soon as I could I left the mountain and the stories behind’ (35). The placing of this story immediately after the previous one, and its return to the past, brings closer this traumatic experience of Colin’s and Amy’s judgements about her cousin in the present, thus highlighting the role of significant events in shaping personal identity and patterns of relating in families. It also illustrates the ways in which individuals react to and process events differently, and why identity and belonging can mean very different things to different people. The recollection of this event reveals to the reader that for Colin, ‘living white’ was a way of escaping deep pain. Yet it was not without consequences; the choice between ‘succeeding’ or ‘failing’ to overcome the past resulted in losses either way. He says:

Years later, when I find myself missing it all, prodding for a different version of me that wasn’t sculpted in anger … it was maybe too late; my grandmother had gone and my mother was an old woman … I wasn’t a bush boy anymore, not a bush man. (35–36)

The fourth story ‘Skin’ takes the reader even further back in time, describing the circumstances of Amy’s father − Charlie’s − birth. The narrative is focalised primarily through Marie, who is portrayed as sensible and responsible in contrast to her sister Pearl, who, heavily pregnant, ‘came wading through the long grass, her hands on the hips of the ironbarks … a dirty weight, belly protruding in her sweaty white dress’ (38). Marie takes Pearl in and continues to look after her even after she discovers her husband Griffin having sex with Pearl in the bathtub. She assists Pearl in labour, soon after which Pearl hands the baby over to Marie to raise: ‘A gift. A birthday present’ (51). Juxtaposed with this experience of ‘parent-swap’ are snippets of Griffin’s backstory. Griffin was bought up by adoptive, white, comfortably middle-class parents, but when he sees an Aboriginal family cooking in a park, he discovered ‘he was hungry’ (42). After ‘Marie, a dust-coloured girl, fed him fish’ he was ‘brought back to life by [those] first few bites’ (42). These parallel stories explore identity literally – who are my parents? where do I belong? – and epistemologically – how does one come to understand what belonging means? Further, they posit that belonging might be forged through continuing yet evolving relational cultural practices: Griffin and Marie ‘named the baby Charles … He wasn’t painted up proper way, and there was no ceremony, the clapsticks had disappeared from the house, but Marie knew he’d grow up Kresinger; she knew how to do it right’ (51). This assertion echoes Martin Nakata’s claim that despite a perceived distance from ‘the traditional context’, Indigenous ways of ‘“doing” knowledge’ (including ways of relating to kin and socialising children) are part of an Indigenous ‘worldview’ (10).

The final and fifth story interrupts time, again, placing the reader initially in Amy’s early childhood, although she does not feature strongly in this story. Her father, Charlie, has had a motor bike accident, and the story weaves the perspectives of two women who are racing each other in separate cars up a mountainous road to his side: his Greek wife Lena (Amy’s mother), and a white-Australian women Janet, with whom Charlie has shared an unresolved connection over many years. As the two women chase and overtake one another they each reflect on their relationship with Charlie: how they first met him and the intervening years. When they reach the accident site their respective declarations reveal what Charlie means to each, now:

‘My husband,’ Lena tried to say, but her voice got caught in her throat when she saw the stretcher.

‘My love!’ Janet’s voice overpowered Lena’s. (61)

Charlie survives the accident and we are told, in brief summary, that after this Lena and Janet ‘developed a fondness and respect for each other’ (63), supporting each other through the dissolution of their marriages, and remaining friends until Lena’s premature death in a different road accident. We see Janet beside Lena’s hospital bed, crying for her friend, but it is Charlie and Amy who bring this story, and the mini short story cycle, to a close, in a picture of the two bound together and haunted by the legacies of three generations of struggle: ‘Every night that month they drove the suburbs looking at the Christmas lights … On stormy nights they both dreamt intensely, violently − they often drowned. Charlie realised it had always been like this, even before Lena had passed’ (64). The reader has come full circle. Through selected, yet interconnected experiences involving different intergenerational members of one family, the reader has a deeper understanding of Amy and her relationship with her father, the complex, interconnected and relational processes that help to shape identities, and some of the diverse experiences of Aboriginal people throughout the twentieth and into the twenty-first centuries. ‘Heat’ thus establishes a pattern of revealing historical connections – the ways that relational ties can be severed, and sometimes healed, and the adaptability and resilience of cultural practices and identities. This in some way foreshadows the possible futures anticipated in part two, ‘Water’, and the fragments of the present in part three, ‘Light’, yet these two sections draw on very different narrative strategies to achieve these ends.

‘Water’: the long story and speculative fiction

While ‘Heat’ looks to the past to explore the origins of the restlessness felt by a younger Aboriginal generation, gothic-influenced ‘Water’ speculates about the future, and examines sexual, personal and familial identities through a very different form, the long story or novella, which structurally complements the emotional distance its protagonist and narrator Kaden traverses when personal and political challenges threaten her sense of self. In addition, drawing on science fiction tropes, such as aliens and chemical genocide, this story evidences the versatility that Neerven employs to explore the breadth of Aboriginal experiences and concerns.

In this imagined future Australia is a republic where the president, Tanya Sparkle, was elected on a tide of popular longing to overcome past injustices. This scenario might extrapolate on some liberal desires to ‘know’ Indigeneity or arrive at solutions to move past uncomfortable truths about Australia’s colonial past, but the superficiality that buoys this fantastic future is grounded in government policy that is ill-conceived, reflecting what Julie McGonegal, drawing parallels between Canadian and Australian contexts, describes as a persistent ‘misrecognition’ of the breadth and continuing impact of colonial genocide (71). In ‘Water’ tokenistic embracing of elements of Aboriginal culture fail to contain the truth that Australian society, yet to grapple honestly with its colonial past, perpetuates ‘willful ignorance’ (McGonegal 71) and violence on Indigenous, and one could add here ecological, communities. Thus, we learn that census data reports that Aboriginal spirituality is emerging as the most popular religion, the national anthem is Jessica Mauboy’s ‘Gotcha’ and the country’s flag ‘looks like Tanya Sparkle’s seven-year old son did it on Paint’ (73). A social media ban has been in place for three years, and people have been gaoled over ‘provocative material, particularly what they call racial violation’ (73). Further, Sparkle has launched an ambitious project to reclaim territory in the Pacific Ocean which will be called Australia2. And yet selected Australians who, ironically, can show ‘they have been removed or disconnected from their country’, will be further displaced and relocated to this new place (74). Echoes of a ‘final solution’ resonate here. The narrator Kaden, a young, lesbian woman, is employed by the project developers as a Cultural Liaison Officer to work with (read ‘win over’) the new territory’s recently discovered indigenous population of ‘sandplants’, a hybrid and androgynous form of plant and human life that has inhabited the territory for thousands of years and whose ‘knowledge goes back, big time’ (113). As the story progresses, Kaden’s developing intimacy with one of these creatures, Larapinta, forces her to re-evaluate her ideas about identity: her ethnicity, sexuality and even her status as a human being. In one conversation with Larapinta, Kaden says:

We find ourselves talking about gender. We are two different societies. She asks me if I feel like a woman, even though I have short hair. I tell her that hair is the least of it. She asks me about my Aboriginal identity. I tell her that it is easy to pretend that I am someone else, but I don’t want to pretend.

‘And your sexual identity?’ She is really in the mood for grilling me.

‘Queer, I guess.’ I say. ‘I know it’s an old-fashioned word …’

‘That is fine. I do not know the common usage of words. They are bricks, aren’t they?’

‘Some words are loaded.’ I continue. ‘Will always be loaded.’ (95)

Kaden’s responses here represent tensions that can arise between understanding of oneself and socially prescribed limitations around identity, especially where the speaker’s subjectivity is a marginalised one. McGonegal remarks of her Canadian First Nation heritage that ‘I am palpably uncomfortable about publicly identifying myself as a mixed-blood person for a host of reasons’ (79). Heiss also explores the ‘complexities’ of Aboriginal identification that ‘have existed since the point of invasion in 1788’ (5) and the resulting ‘importance of the words I choose’ (3). In this moment between Kaden and Larapinta the physical movement towards the other rescinds the use of words. Each step closer literally, intellectually and emotionally, confuses and in part dissolves Kaden’s sense of the differences between them, until the physical and sexual divide is so small that crossing it becomes possible:

I let her in my mouth. What will this experiment hold for her … What will I discover in this uncharted experience? How much of what it means to be human will sway deep in my mind like a ship … To feel she is human now is a lie, I must be with who she is … We embrace each other, cradle the warmth between us. (102)

Sandwiched between the realist and magic realist styles of ‘Heat’ and ‘Light’, ‘Water’ emerges in stark contrast to its neighbours in genre, and the extent to which it forces contemplation on the nature of identity and the boundaries – imagined or otherwise – between different others. As Polak remarks, Kaden’s relationship with Larapinta ‘transcends gender and cultural binaries as the known and unknown collapse into “unalienness”’ (126). And yet my conversations with Neerven inevitably touched on the similarities between ‘Water’ and the Australian Broadcasting Commission’s television series Cleverman, which also draws on gothic and speculative traditions, and also introduces a recently discovered species: humanoids colloquially known as hairies, who have superior strength and apparently stronger connections to the spirit world. Like the fate of the sandplants in ‘Water’, the hairies’ situation reflects the history and complexities of Indigenous experiences under colonisation. For both Kaden and Koen, the young hero in Cleverman, relationships with the other force a re-thinking of their own cultural belonging and responsibilities: socially, culturally and politically. Neerven sees works like ‘Water’ and Cleverman as connected to developments in the Australian gothic, and Aboriginal speculative fiction more specifically. This is a genre that Kwaymullina argues is entirely consistent with traditional and contemporary Indigenous cultures and literatures (27), because ‘we understand the tales of ships that come from afar and land on alien shores … [and we have] lived through the end of the world, but we did not end’ (29).

These genres, Neerven explained, deploy storytelling to imagine alternative futures for Aboriginal people, often by reconfiguring power relationships to bring greater empowerment to Aboriginal people. This involves not necessarily accepting the present as it actually is, but contemplating how events might unfold through an imagined, uncolonised lens. Aboriginal speculative and gothic fictions, then, could be viewed as political interventions. For instance, Katrin Althans describes the Aboriginal gothic as a product arising from the combination of the European gothic and Aboriginal tradition and culture which forms sites of ‘creative resistance’ where ‘issues of Aboriginal culture and identity’ are negotiated (140). Readers are actively involved in these negotiations, challenged by new concepts that extend the sense of what is possible (Polack 23). Thus, at the close of ‘Water’, the position Kaden adopts exemplifies the kind of self-determination made possible by reunification with the ‘old ways’. Standing in solidarity with her kin and the sandplants, Kaden prepares to join the resistance: ‘I step on to the ferry and stand next to my uncle. The water is rising around us and I can feel the force in the leaping waves and what we’re about to do’ (123).

Thus far Neerven’s storytelling has incorporated realist and non-realist modes and diverse narrative structures to capture some of the diversity of Aboriginal experience. Further, the temporal jumps from past to future within ‘Heat’, and between that and ‘Water’, reinforce the notion of identities as relational constructions that link generations and individuals across time and space. In ‘Water’, the languorous nature of the long story encourages the reader to imagine into the temporal distance to contemplate the possibility of society repeating mistakes of the past or finding new ways of being and relating across difference. That the differences are between species in this futuristic Australia serves to confront at a deep level the limits and injustices produced by alienating otherness. The third and final part of Heat and Light brings the reader’s attention firmly back to the present, perhaps a fitting ‘baseline’ on which to leave this expansive picture of identity.

‘Light’: the story collection and mosaic approach

‘Light’ is a suite of ten stand-alone stories that capture an array of protagonists in often brief glimpses into their lives. No two stories or characters are alike. This is Australia in the present: contemporary, mostly urbanised young people negotiating their place in the world where one or more aspects of identity is salient, and issues of family and belonging are always central. According to Neerven, many of these stories draw inspiration from her experiences at university where, as part of a group of Murri students, she developed an intense interest in exploring internalised racism and inter-generational impacts of colonisation, objectives consistent with assessments of Aboriginal writing that identify a persistent and perhaps unavoidable ‘nexus between the literary and the political’ (Heiss and Minter 2). Issues around cultural identity do not always present as the most pressing concerns in these stories: sexual identity, class and position in the family hierarchy are explored as equally important factors in de/stabilising an individual’s self-assurance, as are matters of the heart, with love and sexuality prominent themes. The resulting effect is a mosaic approach to storytelling that creates a sense of breadth – the settings range from east to west, and then north of the country – and indeed light, with the diverse characters’ experiences illuminating and embracing difference. In some ways the range presented in this section of the book raises the most interesting questions for the reader because the meaning of some of the stories is not always immediately clear. ‘Lungs’, for instance, a vignette about two young people stranded during a flood, closes with an ambiguous warning about ‘the contagion of trauma’ (151). Close critical analysis of each individual story would unearth material for greater reflection than is presented here. It is sufficient to acknowledge that the structure of ‘Light’, as traditional story collection, considerably expands the capacity of Heat and Light to fulfil Neerven’s ambition ‘to show as much diversity as I could’ and evidences Neerven’s literary dexterity.

‘S&J’ tells the story of two young women, Ester and Jaye who, while on a road trip up the coast of Western Australia, pick up a hitch-hiking German woman. Sigrid is delighted to meet a ‘real Aboriginal’ (155) and asks Jaye to ‘tell me all about your hardship’ (156), a question that suggests stereotyped assumptions about Aboriginal people are so entrenched they persist beyond inherited representations (Langton 34–35) to those translated intercontinentally. Nevertheless, Jaye encourages Sigrid, who quickly insinuates herself between her companions, throwing into confusion an unspoken understanding between Jaye and Ester and stirring jealousy in Ester that she cannot explain. When Sigrid moves on as suddenly as she arrived, Jaye tells Ester that ‘Sig [was] just a chick’ but ‘You’re my best mate’ (163), but their reconciliation feels incomplete, and hints at feelings yet to be named and claimed. When Jaye asks Ester about a pub concert that Jaye had failed to attend, Ester reflects: ‘I’m not sure how to answer. “Not the same,” I say’ (164).

In ‘Anything Can Happen’, the un-named twenty-year-old narrator is setting up house with her girlfriend, Lucy, making trips to Bunnings for plants ‘because we’re all settled and shit’ (141). A minor domestic tussle over whether to get a new broom illuminates a deeper wrench the narrator feels between her love for Lucy and longing for her mother, Denise, who recently and suddenly took off across the country to Port Hedland. The conclusion does not resolve this conflict but leaves the reader with a picture of the narrator forging an imagined connection with her mother: ‘I bet Mum’s on the beach, shades on so no one knows she’s thinking of a daughter left behind’ (146). ‘Paddles, not Oars’ shows us thirteen-year old Kela, newly homeless and living with his mother in their car. While she sleeps in the back, Kela sits in the driver’s seat. Through snippets of remembered conversations and images, and the sense of power that comes when he grips the wheel, Kela ponders what it might mean to become a man in his father’s eyes. In addition to these, a fourth example ‘Currency’ is an unsettling tale that exemplifies the wide range of genres and styles Neerven exhibits in her storytelling. Park is driving his wife, Blue, and son, Connor, inland, away from ‘the city’s influence … [where] his family will be safe’ (187). When they stop in a small town to rest the family finds things are ‘not what you’d expect’ (188). Money is no good here; physical nourishment and emotional security is obtained through different, almost mystical, patterns of exchange that Park and Blue and Connor will need to learn if a new home ‘out bush’ is to be made. ‘Currency’ toys with and yet challenges the gothic literary tradition that Althans claims ‘shadowed the expansion of the British Empire … thus legitimizing colonial supremacy’ by framing an inhospitable landscape inhabited with ‘strange and exotic monsters’ (142). Park is equivocal about the outback: he seeks its refuge yet sleeps with a gun between his legs. But, fittingly perhaps for a book abundant with youthful representations, it is in the dreams of a child that hope is found: Connor, still small enough to sleep under his mother’s arm, visualises the wild camels as ‘honey coloured with two long horns’, but he knows ‘they will never harm him’ (195).

Through these and many other fragments in ‘Light’ a multilayered picture of contemporary Aboriginality emerges, one burdened with ongoing impacts of past traumas, but also resilient and adaptable. These lived realities represent the common experience of hopes and dreams (for love and acceptance and purpose), and concerns (for familial happiness and security) of these young people, their families and their communities.

Through a tripartite structure incorporating a short story cycle, long story and story collection, and drawing on a wide range of genres and styles, Heat and Light represents some of the diversity of Aboriginal experiences in Australia. Focusing on young Aboriginal protagonists in particular, these stories reflect complex issues around identities that are felt broadly and cross-culturally today and that take into account differences in age, gender, sexuality, class and educational attainment. This flexible approach to storytelling legitimises Polak’s assessment of Neerven as a ‘new literary star’ (121) and goes some way to answering Grossman’s question about the direction that young Australian Indigenous women writers will take Indigenous literatures in the twenty-first century. As Heat and Light shows, the individual texts of contemporary writers very often resist generic categorisation, yet nevertheless maintain strong ties with the fiction and non-fiction traditions from which they have sprung.

Footnotes

-

While I generally use Indigenous when referring broadly to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and cultures, Aboriginal is used throughout where this is consistent with the context of a particular conversation, text or author.

↩ -

I extend my thanks to Ellen van Neerven and Jeanine Leane for their willingness to discuss my ideas for this work and to Jeanine for providing feedback on drafts of this essay.

↩